SpaceX launches European asteroid probe as hurricane weather closes in

Dodging stormy weather ahead of Hurricane Milton, SpaceX launched the European Space Agency’s $398 million Hera probe Monday on a follow-up flight to find out precisely how a moonlet orbiting a small asteroid was affected by the high-speed impact of NASA’s DART probe in 2022.

The launching was in doubt until the last moment, with thick clouds and rain across Florida’s Space Coast, fueled by moisture pulled in by the intensifying hurricane to the west.

Adam Bernstein/Spaceflight Now

But as the launch time approached, conditions improved enough to satisfy launch safety rules and NASA managers cleared the rocket for takeoff. Right on time, at 10:52 a.m. EDT, the Falcon 9’s first stage engines ignited with a burst of flame and the booster climbed smoothly away from the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

extreme winds and torrential rain to Florida’s Space Coast by Wednesday, a forecast that prompted NASA to stand down on plans to launch the agency’s $5.2 billion Europa mission to Jupiter and its ice-covered moon Europa on Thursday.

Instead, NASA announced late Sunday the rocket and it costly payload will remain in a SpaceX hangar at the base of launch pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center until Milton passes by and safety personnel have a chance to inspect spaceport facilities for signs of damage.

The weather also has thrown a wrench into NASA’s plans to bring three NASA astronauts and a Russian cosmonaut back to Earth after a 217-day stay aboard the International Space Station.

Crew 8 commander Matthew Dominick, Mike Barratt, Jeanette Epps and cosmonaut Alexander Grebenkin had planned to undock Monday.

But NASA announced Sunday their departure would be delayed to at least Thursday because of the expected bad weather. Crew Dragon ferry ships require calm winds and seas in the Gulf of Mexico or the Atlantic Ocean to permit a safe splashdown.

Mission to an asteroid and its moon

In the meantime, despite an initially grim forecast, SpaceX was able to take advantage of a break in the weather to kick off Hera’s two-year voyage to the asteroid Didymos and its small moon Dimorphos.

ESA

The DART impact altered the 11-hour 55-minute orbit of the 495-foot-wide Dimorphos, shaving 31 minutes off the time needed to complete one trip around the parent asteroid Didymos. The test confirmed the feasibility of someday nudging a threatening asteroid off course before a possibly devastating Earth impact.

But a successful deflection would depend on a variety of factors, including when the threat was detected — the farther out, the better — and the asteroid’s composition.

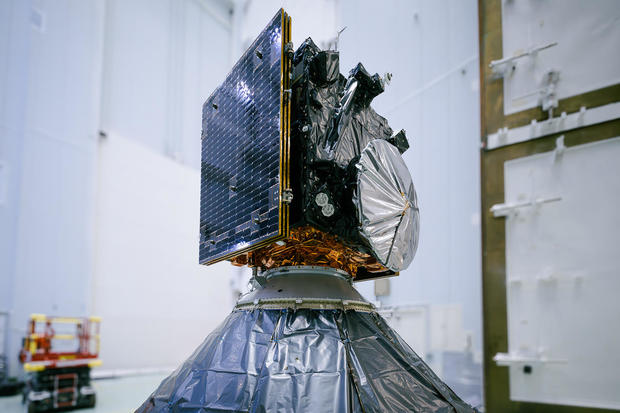

ESA’s Hera probe will orbit the Didymos system and study both asteroids in detail with 11 high-tech cameras and other instruments, deploying two small “cubesat” satellites to study the interior structure of Dimorphos, assess the DART impact crater, the moon’s internal structure and composition.

The goal of the Asteroid Impact and Deflection Assessment, or AIDA, is to better understand the techniques that might be needed to prevent an Earth impact.

“The good news is no dinosaur killer is on its way to Earth during the next 100 years,” said Richard Moissl, director of ESA’s Planetary Defense Office. “We are safe from that scenario, but there are smaller ones, especially in this dangerous size, 50 meters and upwards, where it really threatens human life on the ground.”

ESA

The first step in planetary defense is detection, he said, followed by detailed observations to pin down the asteroid’s orbit and determine whether a collision with Earth is a possibility.

“For small objects, civil protection is the way to go,” he said. “But 50 meters (160 feet across) and larger, you really want this thing not to hit Earth, not to threaten population centers. And then step three comes into play, deflection.

“But again, it’s always good to know what you’re up against. And this is where Hera and DART come into play.”

Unlike most Falcon 9 flights, there were no plans to recover the rocket’s first stage. To give Hera the velocity need to break free of Earth gravity, the Falcon 9’s two stages were programmed to use up all of their propellants, leaving none in reserve for a powered first stage landing.

The flight plan called for two firings of the upper stage engine before Hera’s release to fly on its own one hour and 16 minutes after liftoff.

To reach Didymos and Dimorphos, Hera will have to execute a deep space thruster firing in November to set up a gravity-assist flyby of Mars in March, sailing within about 3,700 miles of the red planet. Along the way, the spacecraft will pass within 620 miles of the small martian moon Deimos.

“By swinging through the gravitational field of Mars in its direction of movement, the spacecraft gains added velocity for its onward journey,” Michael Kueppers, ESA’s project scientist, said on the agency’s website.

“This close encounter is not part of Hera’s core mission, but we will have several of our science instruments activated anyway. It gives us another chance to calibrate our instruments and potentially to make some scientific discoveries.”

After another deep space maneuver in February 2026, Hera will finally be on course to slip into orbit around Didymos the following October. The mission is expected to last about six months.

More

More

Source: cbsnews.com