Selection from the book “Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions” by Ed Zwick

Gallery Books

We may receive a commission for any purchases made from this article as an affiliate.

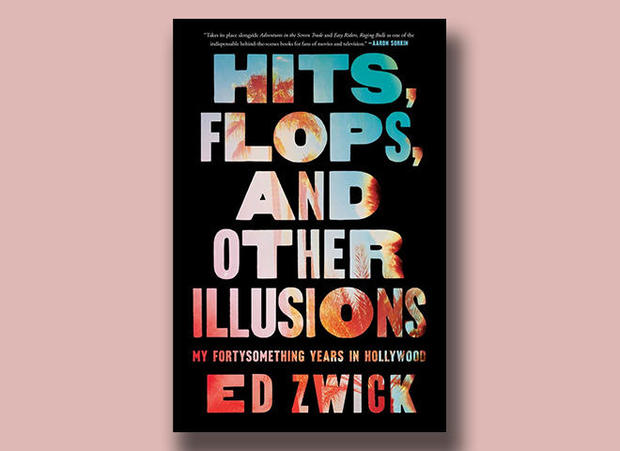

Writer, director and producer Ed Zwick, co-creator of the TV series “thirtysomething,” and who was behind such films as “Glory,” “Legends of the Fall,” “Shakespeare in Love,” and “Blood Diamond,” recounts four tempestuous decades in the business in his entertaining new memoir, “Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions: My Fortysomething Years in Hollywood” (Gallery Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster).

Zwick talks about how he made his Emmy Award-winning television show, “Special Bulletin,” which was a mock news broadcast depicting the detonation of a nuclear device by a terrorist group in Charleston, South Carolina. Some people at the network were not excited about the concept.

On March 3, “CBS News Sunday Morning” aired.

“Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions” by Ed Zwick

Would you rather listen? Currently, Audible is offering a free trial lasting for 30 days.

From Chapter Three: The Year of Loving Dangerously

When I reached the age of thirty, a lot of major events occurred simultaneously. I experienced love, illness, success, and tragedy all at once. Not to mention getting married, making new friends, getting pregnant, and going to therapy – it was a wild mix. One of the challenges of embracing the unpredictability of life is acknowledging that you can’t always be in charge. This is especially difficult when life seems to be crashing down on you like a fast-moving truck in the opposite lane and there’s no way to escape the impact.

I nearly forgot about the deadly car crash. It also occurred.

In 1982, I was feeling stuck in my career. Despite the fortunate opportunity to produce a network TV series at the young age of twenty-seven, my writing was going unnoticed and my TV directing was lackluster. It seemed like there was a gap between my intentions and the final product on page and screen. Even though my friend Marshall and I were inseparable since our days in film school, we often pushed each other to improve and give honest feedback. It was rare to find someone who would always tell the truth, and even more so in Hollywood. Marshall remained my first reader and after he read my new scripts, his compassionate yet pained expression confirmed that it was not up to par. Even after fifty years, his blunt critiques can still irk me. He would simply say, “This part is tiring.”

After experiencing early success with the show Family, I had purchased a small house that I could no longer afford. I then took on any available work in order to make mortgage payments, including a low-budget independent film about the Kentucky Derby. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to attend the actual race or even travel to Kentucky. In the meantime, my colleague Marshall was also struggling, writing for unfulfilling projects such as CHiPs and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. He eventually had to borrow money from his father to write an original script and promised to pay him back with interest if it sold, but unfortunately, it did not. As our writing days became increasingly unproductive, we would often call each other and meet at a video arcade to play a road-racing game. Afterwards, we would lay on the floor of my house, which I was about to lose, and vent about our frustrations. During one of these venting sessions, I shared a nightmare I had about a looming nuclear disaster that left me sweating and struggling to breathe upon waking.

According to him, we need to take action!

“Do what?”

“Present it as a film!”

“I am referring to experiencing severe anxiety, not discussing a business agreement!”

“I’m being sincere,” he stated. “Consider this, what if we were to narrate a tale on television using only what can be seen on the news.”

Are you referring to something similar to Orson Welles’ rendition of War of the Worlds?

“However, we will not consider aliens. Instead, we will select something more believable and frightening.”

“Do you mean it’s similar to nuclear annihilation?”

“We will produce all the footage for the news.”

“Do you like The Battle of Algiers?”

I am not familiar with it.

This was the beginning.

I won’t try to describe the labyrinth we had to navigate before getting NBC to agree to pay us for a script. Had they not been languishing at the bottom of the Nielsen ratings, I’m convinced they would never have given us a chance. The moment we began writing, though, it was as if fortune’s wheel had turned, and our names spun to the top. We couldn’t believe our luck. I imagine the movie gods gazing down on our giddy optimism, chuckling, So they want to disrupt the universe? Let’s see how much disruption these two geniuses can handle …

Here are some of the things that happen that year, 1982:

The following day after we start writing, I encounter a young woman in the parking lot of the former Santa Monica shopping center. My damaged vehicle is being repaired, so I have borrowed a friend’s car and now can’t recall where I left it. She is operating a run-down car from Dave Schwartz’s rental company and also cannot remember its appearance. We engage in conversation while searching for our vehicles on different levels. Before she locates her car (which holds a copy of Pascal’s Pensées on the passenger seat), I am able to obtain her phone number.

I inform Marshall about the woman in the parking lot, expressing my admiration for her beauty, wit, and intellect. I confess that I may be falling in love with her. He responds with, “What’s new? You say this every other week. Let’s get back to work.” The following day, I try to reach out to the woman, but discover she is already in a relationship. I have no choice but to refocus on work. Several days later, Marshall reveals that his now-wife Susan is pregnant with their first child. He is too preoccupied to work. The next week, the parking lot woman, named Liberty, contacts me to inform me that she has left her partner. Both Marshall and I are too elated to focus on work. We all spend a blissful summer watching Susan’s pregnancy progress. I propose to Liberty, and she accepts. Marshall and I finish a first draft.

In September, we receive word from the network that they are pleased with our work. However, the following day, Marshall receives distressing news that his father has been diagnosed with a brain tumor. The outlook is not positive, and Marshall quickly travels to Philadelphia to visit him. Later on, he joins us at Liberty’s farm in rural Pennsylvania to serve as my best man at the wedding. On the day of the ceremony, we are informed that the network wants us to visit New York City to observe NBC News. After the wedding, Susan returns to Los Angeles while Liberty, Marshall, and I head to Manhattan for our honeymoon. The next morning, we begin our observations at NBC News.

In the middle of November, the rewriting process is completed. Two weeks later, the network grants us permission and things move forward quicker. We initiate preparations in Los Angeles and cast relatively unknown actors as the idea only works if the audience is not familiar with them. (This is how we are introduced to David Clennon, who would later portray the infamous Miles Drentell in thirtysomething.) During rehearsals, I take on the role of the news cameraman and operate the video camera myself. Upon reviewing the footage, I am thrilled to see that my vision has been brought to life exactly as I had imagined. That night, I am consumed with excitement and unable to sleep, thinking that I may have a career as a director. The following day at the production office, I receive a call from my sister informing me that my mother was killed in a car accident. I break down in tears in the arms of my colleague, Marshall.

That evening, I make my way back to Chicago in order to assist my sisters in preparation for our parent’s funeral. My siblings have already felt the impact of our parents’ messy divorce, but now they are completely devastated. I want to offer them the support they need, but the truth is, I am struggling to hold myself together. The day after my mother’s funeral, I travel to Charleston, South Carolina to meet with Marshall and scout locations for our upcoming project. Despite my grief, I channel my energy into work, a coping mechanism that has served me well in the past. We begin shooting in January, and although it is a physically and emotionally grueling experience, we are determined to see it through. However, on the first day of filming, our lead actress is struggling – whether it is due to nerves or a medical issue, her voice is not suitable for a professional news anchor. Marshall and I huddle together, realizing we may have to let her go. This is a daunting task for me, as I have never had to fire anyone before. While I try to focus on directing, knowing we will have to reshoot everything, Marshall is frantically searching for a replacement. We ultimately choose Kathryn Walker, who receives the script at 7 p.m., reads it by 9 p.m., and arrives on set at 4:30 a.m. the next morning. She is flawless and brings brilliance to her performance. Kathryn Walker is nothing short of a goddess.

After completing production, the network informs us that they require our film, which is now titled “Special Bulletin,” to air within six weeks. Unfortunately, there is currently no technology available for editing videos that allows for the flexibility used in film editing. Additionally, there are no film editors with training in video editing systems. This means that we must edit the movie online, with minimal assistance from a news editor who may not be familiar with storytelling techniques. My colleague Marshall and I work tirelessly in a facility in Burbank, carefully making decisions for each scene one by one, in chronological order. Sometimes, we have to start over again if something doesn’t work. In the middle of this editing process, my colleague Susan goes into labor. Despite being sleep-deprived and barely recognizable, Marshall returns to the editing room two days later to work on the offline version of the “news packages” that will be inserted into the final cut, which I am currently completing.

The television program is scheduled to be broadcast in two weeks, however, before that can happen, Reuven Frank, the leader of NBC News, demands to watch the film and becomes extremely upset. He contacts Brandon Tartikoff, the NBC president, and insists that the film not be broadcasted. He is worried that the portrayal of a nuclear event, filmed to look realistic, could not only cause mass panic, but also damage the reputation of the news department. As soon as we learn that the network is seriously considering not airing the film, we inform Howard Rosenberg from the L.A. Times and John O’Connor from the New York Times about the situation. They request to view the film. Following the philosophy of Werner Herzog, to seek forgiveness instead of permission, we send it to them without the network’s permission. Chaos ensues as the controversy is featured on the front page of every media outlet in the country. Everyone is eager to watch the film that the network is refusing to air. Tartikoff has no choice but to broadcast it, however, to appease the news division, he agrees to include a disclaimer at the bottom of the screen after each commercial break. Although we are not pleased with this decision, most people do not pay attention to them as they are preoccupied with getting food during the commercials.

The pace of events is unyielding. There are glowing reviews followed by six nominations for an Emmy, including for best movie, writing, and directing. Just two days before the awards ceremony, Marshall’s father passes away. He rushes back from the funeral in Philadelphia, barely making it in time to put on his new tuxedo and accept a handful of Emmys. A few days later, Liberty surprises me with the news that she is pregnant. I am overwhelmed with joy, but also stunned. Confused after giving yet another speech for an award – it could have been for the Writers Guild, the Directors Guild, or even the Peabody – Marshall and I find ourselves sitting outside the Beverly Hilton, holding onto our small statues. I don’t know whether to laugh or cry. Marshall turns to me, or perhaps it was the other way around, and in a humorous Yiddish accent asks, “So, what’s up…?”

It was a mixture of darkness and humor, but eventually we ended up laughing uncontrollably to the point of tears. Onlookers couldn’t help but stop and stare at the two bearded men in poorly fitting tuxedos doubled over in fits of both amusement and sorrow. For a whole year, just as we were recovering from one overwhelming experience, another one would come crashing down on us. Was this how adulthood would always be? It felt like Newton’s third law of motion in action: for every triumph, there would be an equal and opposite tragedy. We were beginning to understand that in life, it’s never just one thing or another – it’s always a combination of both. This thought would later become a sort of motto for our creative pursuits.

The publication “Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions: My Fortysomething Years in Hollywood” by Ed Zwick was released in 2024 and is copyrighted by Edward Zwick. It is being reproduced with permission from Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

The book can be obtained here.

“Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions” by Ed Zwick

Buy locally from Bookshop.org

For more info:

More

Source: cbsnews.com